In the trading world, no one operates in isolation; the financial market is an ecosystem made up of diverse players. Every buy or sell order has some market participant behind it, from the individual trader at home to massive financial institutions. Knowing who these participants are and how they operate is fundamental to understanding how markets work and to improving our own trading strategies. In this chapter, we will explore the main market players: the retail trader, institutional participants, prop firms, and brokers, examining what each one does, how they interact with each other, and why understanding their roles is important.

What Is a Market Participant?

A market participant is anyone or any entity that takes part in the buying or selling of financial instruments. This ranges from individuals (like you, if you invest or trade with your own money) to huge organizations like banks, investment funds, or specialized trading firms. All of them, big or small, are part of the mechanism that moves prices every day. Essentially, if someone executes a transaction in the market – whether buying stocks, selling currencies, or trading futures contracts – they become a participant in that market. Understanding this variety of actors gives us a clearer view of why prices move and who might be behind certain market movements.

The Retail Trader: The Individual in the Market

The retail trader is the individual trader who operates in financial markets using their own capital. Unlike the large players, they typically trade through online platforms from their computer or mobile device traderprofesional.com. While each retail trader moves relatively small amounts of money, collectively millions of retail traders worldwide provide liquidity to markets, helping keep trading continuous and contributing to efficient price formation. In fact, with the proliferation of accessible trading platforms and low entry barriers, individual traders have emerged as a significant force capable of influencing traditional market dynamics.

A retail trader aims to profit from price fluctuations in assets like stocks, currencies, commodities, or cryptocurrencies. Their access to the market is usually through a retail broker, which allows them to trade with relatively little starting capital; thanks to this, even traders with small accounts can use tools like leverage to amplify their exposure. It’s important to note, however, that the total volume generated by retail traders is very low compared to that of professional financial institutions. Even so, the popularity of retail trading has grown rapidly, especially in the past decade, showing that financial power isn’t solely in the hands of big institutions. Recent events have demonstrated that, under certain circumstances, the collective actions of many retail traders (often coordinated through social networks or online forums) can noticeably move the price of some assets.

Institutional Participants: The Giants of the Market

Under the category of institutional participants we find the heaviest and largest players in the market. These are professional entities that manage large sums of money and execute high-volume transactions. This group includes banks (commercial and investment banks), investment funds (like mutual funds or pension funds), hedge funds, insurance companies, asset management firms, and even central banks and governments. Their influence on the market is considerable due to the capital they control and the information and technology resources at their disposal.

Investment and commercial banks are key protagonists. For example, global banking giants such as JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, or Deutsche Bank are very active in markets, whether by facilitating transactions for clients or by trading for their own accounts. In fact, it’s estimated that around 25 major banks – including Deutsche Bank, UBS, HSBC, Barclays, and JP Morgan Chase – account for the bulk of daily transaction volume in markets like foreign exchange. These institutions have specialized trading desks capable of moving hundreds of millions of dollars in moments, and their trades can even influence price trends given their sheer size.

Alongside banks are asset managers and investment firms. Here we find, for example, companies like BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, with about USD 9.42 trillion in assets under management as of mid-2023. Firms like this handle enormous portfolios on behalf of their clients (be they individuals, corporations, or governments) and invest across global markets. Their goals are often to achieve long-term returns, manage risk, and fulfill obligations to their investors. Other examples of institutional participants include well-known hedge funds that seek absolute returns through sophisticated speculative strategies, and sovereign wealth funds (owned by governments) that invest national surpluses in international markets.

The advantage of institutional participants lies in their scale and resources: they have teams of analysts, access to extensive or real-time information, advanced trading algorithms, and the capacity to execute large orders without drastically affecting liquidity. Their decisions can move markets; for instance, a single large buy or sell order from a major fund can push a stock’s price up or down. Therefore, they’re often considered the “smart money” or “whales” of the market. However, they also have constraints and different objectives (many are managing other people’s money with long-term horizons or must adhere to strict regulations), so they don’t always seek the same short-term opportunities that an individual trader might.

Prop Firms: Trading with Proprietary Capital

In recent years, the so-called prop firms (short for proprietary trading firms) have gained visibility. These companies engage in trading with their own capital, meaning they use their own money to make market transactions, as opposed to managing external clients’ funds. Traditionally, prop trading took place within investment banks or hedge funds that allocated some of their resources to speculative trades for the firm’s own profit. However, today the term prop firm is also commonly associated with independent companies that recruit traders and provide them with capital to trade, sharing the profits.

The basic concept works as follows: a proprietary firm provides funds for skilled traders to trade with, and in return the traders split a percentage of the profits they earn with the company axi.com. In this way, a trader can access much larger amounts of capital than what they personally have, boosting their potential gains (while also carrying the responsibility of managing that money under the firm’s risk rules). For the prop firm, this model is an opportunity to earn returns on its resources by leveraging the skills of multiple traders.

For example, it’s common for these companies to offer programs where an aspiring trader must prove consistency and risk control during an evaluation phase; if they pass, they receive a funded account with the firm’s capital (say $50,000, $100,000 or more) to start trading. From then on, any profits made are split according to a predetermined ratio (for instance, 20% to the trader and 80% to the firm, or vice versa, depending on the company). It’s worth noting that prop trading isn’t exclusive to small firms: banks like Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley historically had prop trading desks, and quantitative funds or high-frequency trading firms also fall under this category when they trade with their own money.

For individual traders, prop firms offer a path to overcome personal capital limitations by providing professional tools, mentorship, and greater “firepower” in the market. In turn, prop firms assume the risk of the traders’ activities but enforce strict controls (such as loss limits, known as maximum drawdowns, etc.) to protect their capital. It’s important to clarify that we won’t mention specific prop firm names here, but it’s a growing sector with many companies competing to attract promising traders.

Brokers: The Bridge Between Trader and Market

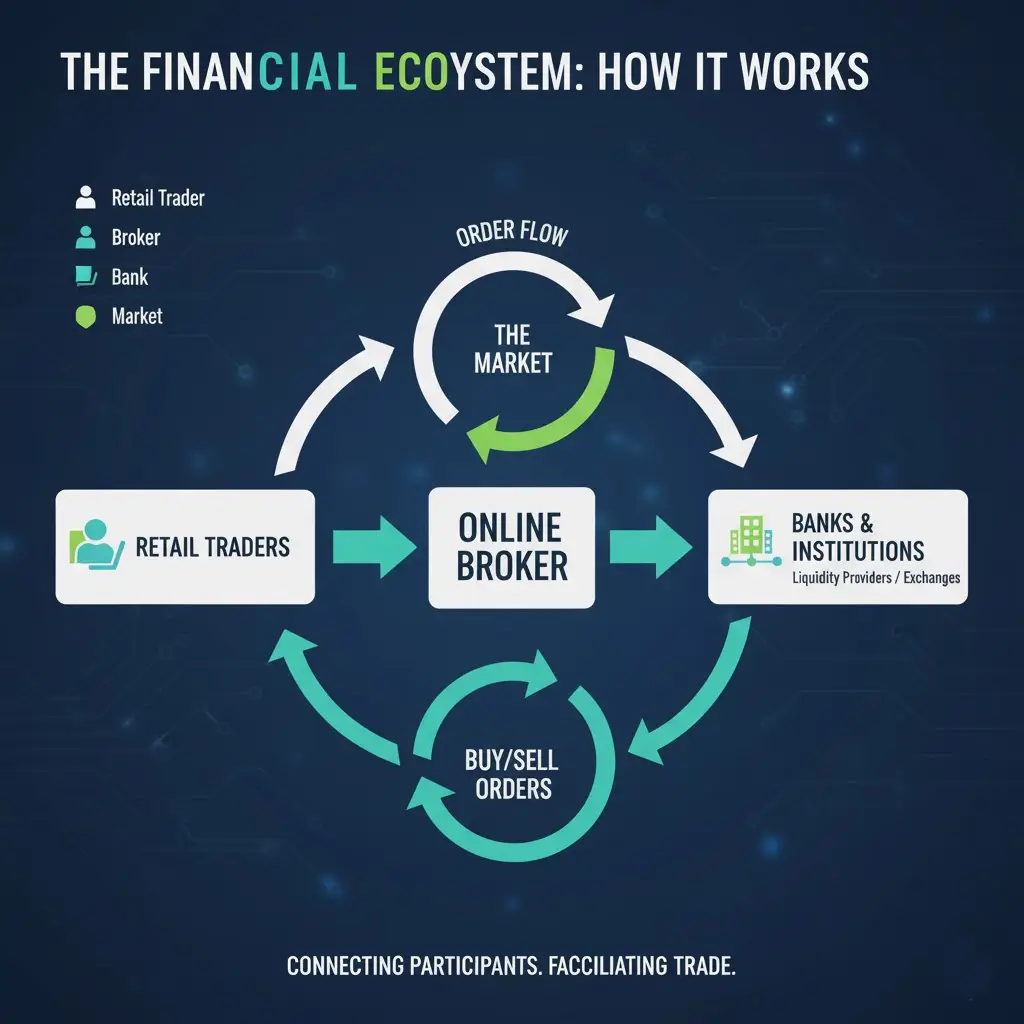

Brokers are intermediaries that facilitate traders’ and investors’ participation in financial markets. When a retail trader wants to buy or sell, say, a stock or a currency, they don’t directly trade on the exchange or interbank market; instead, they go through a broker who executes that order on their behalf. In other words, the broker provides the platform and access to the market in exchange for a fee or spread (the difference between the buy and sell price).

There are different types of retail brokers based on how they handle their clients’ trades:

- Market Maker Brokers: These brokers act as the counterparty to their clients’ trades. Rather than sending every order to the external market, they sometimes “create an internal market.” In practice, if a trader buys, the broker sells to them, and vice versa. This way, the broker profits from the spread and effectively takes the opposite side of the client’s trade. Such brokers usually offer fixed spreads and instant execution, but there is a potential conflict of interest: the broker could benefit when the client loses, since the broker is the one taking the other side of the trader.

- STP Brokers (Straight-Through Processing): These are no-dealing-desk brokers that pass their clients’ orders directly to the market or to external liquidity providers. They do not act as the counterparty, but rather as a bridge. They typically offer variable spreads and make money by charging a small commission per trade or by slightly marking up the spreads they receive from liquidity providers. By not taking the opposite side of trades, they minimize conflicts of interest.

- ECN Brokers (Electronic Communication Network): These brokers connect their clients’ orders to an electronic network where many participants (banks, institutions, other traders) trade with each other. An ECN broker essentially places the client’s order into a global order book, trying to match it with the best available counterparty. This often results in very tight spreads (sometimes near zero, with the broker adding an explicit commission) because clients access the real interbank market prices. Also, since the broker is only intermediating and not taking positions against clients, there’s no conflict of interest with the trader.

Regardless of the type, all brokers must be regulated and operate transparently, as they handle their clients’ money and orders. Some provide proprietary trading platforms or use popular ones like MetaTrader, and they offer real-time data, analysis tools, and educational support. There are also full-service brokers (offering advice, portfolio management, etc.) versus discount online brokers (providing only execution with low fees). For a beginner trader, understanding the differences between brokers is vital in choosing where to open an account, as it affects trading costs, execution speed, and fund security.

How These Market Participants Interact

Now that we know the main participants, it’s important to see how they interact within the financial ecosystem. Think of the market as a large ocean: in it swim everything from small fish (retail traders) to giant whales (institutions), and all play a role in the financial food chain.

- Retail traders and brokers: A retail trader rarely trades directly against another specific retail trader. Usually, their orders are funneled through a broker. If the broker is a market maker, it may take the other side of the order. If it’s STP/ECN, the order goes out to a larger market. In that case, the counterparty to the retail trader’s order may end up being an institutional participant taking the opposite position. For example, if you buy 1 lot of EUR/USD through your ECN broker, you might effectively be “buying” those euros from a bank or fund that was willing to sell in the interbank market. In this way, individual traders gain access to the immense liquidity provided by banks and institutions via the brokers’ intermediation.

- Institutions vs. institutions: Large players frequently trade with each other. In organized markets like stock exchanges, when a pension fund buys a huge block of shares, the seller is likely another institutional investor (for example, another fund or a bank) choosing to liquidate holdings. In the currency market, international banks trade among themselves directly or through electronic systems (such as EBS or Reuters platforms). Also, central banks may intervene by buying or selling massive amounts against other banks to influence their currency’s value. This interplay among giants sets the main market trends in the long run.

- Prop firms in the ecosystem: Prop firms, by providing capital to traders, act as a bridge between individuals and the institutional market. When a prop firm trader executes a trade, depending on how the firm operates, that order can be reflected in the broader market (for instance, if the firm routes orders through a broker or directly to an exchange). In many cases, prop firms use external brokers or liquidity provider arrangements to execute their funded traders’ orders, so effectively they are injecting orders into the market just like any other institutional participant. The difference is that behind those orders is a profit-sharing model and internal risk control. In the ecosystem, prop firms stand as professional players adding liquidity and volume, somewhere between retail individuals and traditional institutions.

- Brokers and institutions (liquidity): Many retail brokers get their pricing and liquidity from institutional participants. For example, a Forex ECN broker connects to a network where banks and large liquidity providers (often trading divisions of banks) continuously offer quotes. The broker aggregates these quotes and shows its traders the best available bid/ask. When clients execute orders, the broker matches them with available institutional counterparties. In contrast, a market maker broker might choose to absorb small clients’ trades internally, but even they tend to hedge their risk in the wholesale market if their clients’ positions become too imbalanced (for instance, if too many clients are buying EUR/USD, the broker might buy EUR/USD from a bank to offset its exposure). Brokers also use prime brokers (usually large banks) to access the interbank market on behalf of themselves and their institutional clients. Ultimately, brokers connect retail traders to the institutional network, and sometimes act as a buffer layer between the two.

In summary, all these actors are interconnected: the prices we see on our screens are the result of interactions between institutional order flows, the decisions of countless individual investors, and the global dynamics of supply and demand. A central bank announcement can prompt institutions to rebalance portfolios, moving prices and affecting both prop traders and retail traders. At the same time, trends sparked by retail investor communities can force funds to react. The market is, in truth, a constant conversation among participants of different sizes and goals.

Know the Players to Understand the Market

Understanding who the market participants are and what motivates them gives traders an important educational edge. Knowing, for instance, that a sudden price movement might be due to the action of a large fund or a central bank (and not just “randomness” or inexplicable manipulation) helps us interpret charts more effectively. Similarly, recognizing that retail traders sometimes get carried away by short-term news or emotions, while institutions might have long-term plans or hedging strategies, allows us to put daily volatility into context.

By knowing the market participants, we can ask critical questions when analyzing the market: Who might be buying at this price level and why? Is it a wave of retail traders chasing a trendy news story, or is it smart money (institutional capital) taking strategic positions? Such considerations can influence our strategies. For example, many individual traders try to identify what the “smart money” is doing in order to align with it rather than fight against the tide.

Additionally, learning from institutional practices – like rigorous risk management, the use of fundamental information, or diversification strategies – can improve our own trading. Understanding how a broker executes our orders makes us aware of possible hidden costs or slippage in low-liquidity conditions, preparing us to manage them.

In essence, the market is complex but not chaotic; it’s made up of humans and organizations of varying sizes and motives. Getting to know this trading “who’s who” is an essential part of the fundamentals for any aspiring trader. It provides a broader, more professional perspective to navigate the financial ocean.